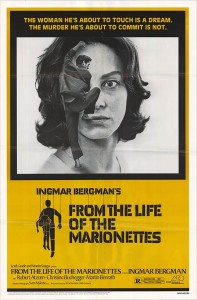

From the Life of the Marionettes (Aus dem Leben der Marionetten) (Ingmar Bergman) (1980)

From the Life of the Marionettes (Aus dem Leben der Marionetten) (1980)

Directed by: Ingmar Bergman in 1980

A young upper class man, brilliant and married to a beautiful woman, murders, without any evident reasons for doing so, a prositute. He is incarcerated inside a criminal asylum, where the judge, the psychiatrist, the man’s wife and his friends try to understand the reason for the man’s insane act, but every explaination seems to invalidate the previous one.

“Life of marionettes” is the only movie which Bergman shot entirely in Germany and it was originally thought as a part of a bigger and more ambitious opera.

Bergman takes two minor characters from “scenes from a marriage”, Peter and Katarina, to bring life into this obscure tale, with strong influences from the visionary work of August Strindberg and the mileu of european existentialism, in particular Kierkegaard and Heidegger.

Like a lot of other Bergman’s movies, the main focus is on the inner life and it’s flow, remarked by the tasty black and white used during all of the movie with the exception of it’s very beginning and ending, the fragmented and irregular pace of narration and the fragmented order, both in space and time, in which the story unfolds. The camera often stops on faces and a lot of screen time is spent on long dialogues, which often are more like long monologues, evidentiating the excruciating lack of real communication and empathy in human relationships and the emotional void and scars that are bringed upon.

Bergman examines this mistery not to find a “solution” (even the main fact remains, after all, an open enigma) but to dwell inside the absurd itself and portray, in an open way, some aspects of the human condition which the extreme cases, like the one narrated here, bring to evidence. Just like in the medical field, the condition of disease is an extreme inflation or distortion of something that’s present even in the state of normal health.

Emotional loss, failure in relationships, the ambiguity of feelings, the mix of hate and love, the contradictory desire to hurt and heal the loved one at the same time, little vengeances that cut deep in silence, failure to communicate and to understand because of personal convinctions and social conventions, which become like thick walls: Bergman does not separe the darker side of life and the inherent problematicity which emerges from it’s investigation from it’s very essence and it’s bright, joyous, side.

Peter, the necrophile homicidial, desires to detach from it all and to deny his very own inner dimension, dismissing his deep interior suffering as a product of a simple hormonal inbalance.

However, even if he is not capable of understanding and listening his heart, he unconsciously acknowledges that it is the true source of freedom and the only “true” reality. In one of the most striking and beautiful sequences of the movie this contradiction is enacted: Peter finally lives in a dream a totally satisfying, compassionate, sensual and embracing encounter with his wife. The dream is not totally free of a dark side, it is at the same time a desire of life and freedom and an inner longing for death and refusal of life, because of it’s oedipical quality.

Swiss psychoanalyst CG Jung wrote about the fundamental ambiguity of images like this, expanding the Freudian point of view and breaking with Freud himself, in one of his most important books, “Symbols of transformation”: the image of the return to the womb can be both regressive and progressive and the path to individuation (and thus real interior freedom) passes through a confrontation and immersion in the primordial inner images and is not devoid of perils and struggles.

Peter, when forced with a sincere confrontation with himself, drowns in his struggle and finally commits the grisly homicide, maybe helped paradoxically by a kind and compassionate gesture of the prostitute (which has the same name of his wife) and by a feel of closure and carceration, similar to his own inner state.

However, even the instrument of psychoanalysis is used by the doctor, who adopts a reductionist approach, in the movie as some kind of exorcism and as a way to objectivize and keep away the other, closing the “case” and with it the frail contact with the human heart and the unknown which lies beneath. Like Heidegger would say this kind of objectivizing approach “is exact but not true”.

The film closes with the desolating view of Peter closing in a total apathy and playing computer chess in prison, until the depressing “you missed the mate” writing on the computer screen closes the door to Peter’s mind and the whole story, while a rock song, the same played in the squalid set of prostitution, starts playing along the final credits, remarking the overall feel of alienation and solitude.

Other recurring Bergman themes appear in this opera: the role of sexuality as an aim of deep and true contact and it’s link with human interiority and the constant attention to the human’s heart and the overall coral effect of the character’s psychology, like every one of them would partecipate to an unique fundamental reality and bring to light something that belongs even to the other, even if hidden (this one too, is a very strong heideggerian influence).

Bergman aims to make the audience feel the voice and the beauty of what is fundamental but lacking, in spite of the abyss in which his characters live in and this remarks the open and humanizing quality of his work and refutes the nihilism and one-sided bleakness which is often credited to him.