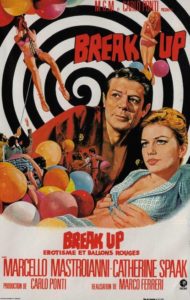

Break Up (Marco Ferreri) (1965)

Directed By: Marco Ferreri in 1965

Break Up is a very rare movie shot by Marco Ferreri in the early ’60s, with a difficult distribution history. At the beginning the producer, Carlo Ponti, decided to cut it down to 25″ and to insert in a movie composed by three episodes shot by three different directors, “Oggi, domani e dopodomani” (“The Man, the Woman and the Money”), as “L’uomo Dei Cinque Palloni” (“The Man With The Balloons”).

After some time, it was re-released in France, got a small release in USA (an English language version has been released) and shown sparsely in Italy in it’s original form, but has always been a very rare movie and a commercial flop. A real pity, given the high quality work that it is.

The plot is focused around Mario, played brilliantly by a very measured Marcello Mastroianni, a entrepreneur in the world of candies, one of the most unsympatethic and selfish main characters that I’ve saw on a movie screen. He’s totally self-centered, cynical, harsh, obsessed with control and money making, not capable of any form of loving or altruism. This is a first hint of how much “Break Up” has been a totally anti-commercial movie, a very critical and provoking work disguised in the form of a comedy.

Mario, by chance (he wants to put a small Christmas gift in his packs of candies to attract the children more towards his products) becomes obsessed by how much air can a balloon take before breaking up. The impossibility to control this little detail cracks his perfectly mechanical life and the weight of uncertainty crushes him. Measuring how much can a balloon take before popping becomes his obsession, his only ever present thought to the point of trascurating his personal affairs and business, leading to madness.

Ferreri tells this tale with a very experimental direction, heavily influenced by surrealism (that already permeated a lot of his early works) and the pop art of the times and wants to convey, through the case of Mario, a portrait of a mechanical and artificial society, which it’s precision is matched by it’s inhuman cruelty.

Like many of his other works, this one has a very sharp and corrosive subtle humor in it, even the soundtrack is, at some extent, sarcastic. The spectator is constantly exposed and engaged by it, in a true provocative fashion.

We can appreciate here the two faces of the obsessive phenomena, being at the same time a defense, focusing one’s attention in only one aspect of life thus not realizing the emptiness and futility of how Mario conducted his life up to this point, and potentially liberating, in Mario’s case by exposing the illusion of a perfect control on one’s life. Ferreri is really brilliant in portraying this duality.

Mario’s life is a very harsh life, hidden by the facade of wealth. He’s totally dominated by his drive to achieve success and gives value to himself only if he’s a winner (“…because if I can’t do it, I’m a complete moral failure inside myself!”), his relationship with others are guided by psychological violence, cynism and exploitation. His only aim is to produce and consume, up to obsession but without a real goal or participation to life.

If Mario’s life is empty, the collective way of conducting it suggested by the society is too: the city life is portrayed as ever-moving, fast, chaotic, filled with vehicle’s pollution. There is little, if any, space for art, contemplation, beauty. All the characters exploit one other, there aren’t any real sympathetic relationship, even the one between Mario and his dog is somewhat spoiled at times.

The society seems to be guided by a cannibalistic instinct: constantly to have more, to consume more, as a mask and defence until self destruction. The theme of eating, like other Ferreri’s movies (in particular the later “La Grande Bouffe”) is very present. Abuse of food as a symbol of consumption (“Sure, they eat a lot! They eat

and then they forget everything. Better than cocaine!”) and a way to fill a fundamental void. What can feed and sustain life becomes excessive, harming.

However, the obsessive fetishes for sex, money and consumption can not ultimately deny and put away completely the madness in the system (portrayed dyonisically in the wonderful psychedelic color sequence of the party) or put a stop to cynism and overall negativity. They can only mask them for a short period of time, until the effects detonate.

Even the tragedy of death becomes a chance of buying, selling, accumulating (a man, whose car has been smashed by a suicide, complains only about his car; a bidder exploits the suicide to try to sell some of his unwanted stuff by telling that those things caught the suicidal’s attention etc). It’s a very strong point and makes one think.

In conclusion, a little exploration of the use of the balloon as a symbol. It summarizes all the points made by the movie in a very clever way: the excess (inflate until explosion), the vacuity (it’s filled by air) and the evasive superficiality (it floats in the air).

Overall, an excellent corrosive work. It deserves a watch, in spite of some occasional repetitions.